Crushing

You managed to intercept a message between two event organizers. Unfortunately, it’s been compressed with their proprietary message transfer format. Luckily, they’re gamemakers first and programmers second - can you break their encoding?

Files:

Writeup by: Hein Andre Grønnestad

Checking Provided Files

$ unzip rev_crushing.zip

$ cd rev_crushing

$ file crush

crush: ELF 64-bit LSB pie executable, x86-64, version 1 (SYSV), dynamically linked, interpreter /lib64/ld-linux-x86-64.so.2, BuildID[sha1]=fdbeaffc5798388ef49c3f3716903d37a53e8e03, for GNU/Linux 3.2.0, not stripped

$ file message.txt.cz

message.txt.cz: data

I guess message.txt.cz was created using the crush program. Let’s try to figure out what it does.

Dynamic Analysis

Running crush

$ ./crush

d

^C

The program is waiting for input.

strace

$ strace ./crush

execve("./crush", ["./crush"], 0x7ffda3248e90 /* 31 vars */) = 0

brk(NULL) = 0x55649079c000

# ...abbreviated

getrandom("\x17\x86\x57\x6c\x45\x22\x17\xbc", 8, GRND_NONBLOCK) = 8

brk(NULL) = 0x55649079c000

brk(0x5564907bd000) = 0x5564907bd000

read(0,

strace confirms this as well. We’re stuck at read.

Static Analysis

Using r2

$ r2 crush

Warning: run r2 with -e bin.cache=true to fix relocations in disassembly

[0x00001070]> aaaaaa

[x] Analyze all flags starting with sym. and entry0 (aa)

[x] Analyze function calls (aac)

[x] Analyze len bytes of instructions for references (aar)

[x] Finding and parsing C++ vtables (avrr)

[x] Type matching analysis for all functions (aaft)

[x] Propagate noreturn information (aanr)

[x] Finding function preludes

[x] Enable constraint types analysis for variables

[0x00001070]> pdf@main

; DATA XREF from entry0 @ 0x108d

┌ 112: int main (int argc, char **argv, char **envp);

│ ; var int64_t var_810h @ rbp-0x810

│ ; var uint32_t var_ch @ rbp-0xc

│ ; var int64_t var_8h @ rbp-0x8

│ 0x000012ff 55 push rbp

│ 0x00001300 4889e5 mov rbp, rsp

│ 0x00001303 4881ec100800. sub rsp, 0x810

│ 0x0000130a 488d95f0f7ff. lea rdx, [var_810h]

│ 0x00001311 b800000000 mov eax, 0

│ 0x00001316 b9ff000000 mov ecx, 0xff

│ 0x0000131b 4889d7 mov rdi, rdx

│ 0x0000131e f348ab rep stosq qword [rdi], rax

│ 0x00001321 48c745f80000. mov qword [var_8h], 0

│ ┌─< 0x00001329 eb20 jmp 0x134b

│ │ ; CODE XREF from main @ 0x1357

│ ┌──> 0x0000132b 8b45f4 mov eax, dword [var_ch]

│ ╎│ 0x0000132e 0fb6c8 movzx ecx, al

│ ╎│ 0x00001331 488b55f8 mov rdx, qword [var_8h] ; int64_t arg3

│ ╎│ 0x00001335 488d85f0f7ff. lea rax, [var_810h]

│ ╎│ 0x0000133c 89ce mov esi, ecx ; int64_t arg2

│ ╎│ 0x0000133e 4889c7 mov rdi, rax ; int64_t arg1

│ ╎│ 0x00001341 e80ffeffff call sym.add_char_to_map

│ ╎│ 0x00001346 488345f801 add qword [var_8h], 1

│ ╎│ ; CODE XREF from main @ 0x1329

│ ╎└─> 0x0000134b e8e0fcffff call sym.imp.getchar ; int getchar(void)

│ ╎ 0x00001350 8945f4 mov dword [var_ch], eax

│ ╎ 0x00001353 837df4ff cmp dword [var_ch], 0xffffffff

│ └──< 0x00001357 75d2 jne 0x132b

│ 0x00001359 488d85f0f7ff. lea rax, [var_810h]

│ 0x00001360 4889c7 mov rdi, rax ; int64_t arg1

│ 0x00001363 e8e2feffff call sym.serialize_and_output

│ 0x00001368 b800000000 mov eax, 0

│ 0x0000136d c9 leave

└ 0x0000136e c3 ret

[0x00001070]>

[0x00001070]> afl

0x00001070 1 43 entry0

0x000010a0 4 41 -> 34 sym.deregister_tm_clones

0x000010d0 4 57 -> 51 sym.register_tm_clones

0x00001110 5 57 -> 50 sym.__do_global_dtors_aux

0x00001060 1 6 sym.imp.__cxa_finalize

0x00001150 1 5 entry.init0

0x00001000 3 23 sym._init

0x000013d0 1 1 sym.__libc_csu_fini

0x00001155 7 161 sym.add_char_to_map

0x0000124a 7 181 sym.serialize_and_output

0x000013d4 1 9 sym._fini

0x00001370 4 93 sym.__libc_csu_init

0x000012ff 4 112 main

0x000011f6 7 84 sym.list_len

0x00001030 1 6 sym.imp.getchar

0x00001040 1 6 sym.imp.malloc

0x00001050 1 6 sym.imp.fwrite

[0x00001070]>

We can see some interesting function symbols.

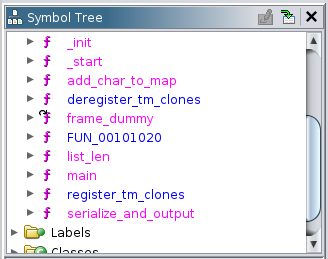

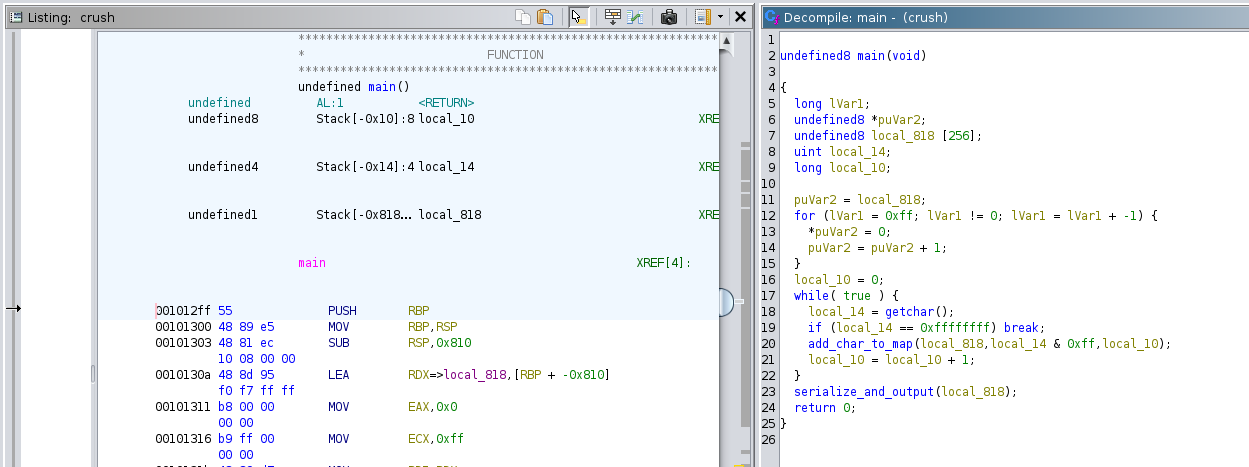

Ghidra

We can see the same symbols.

main seems to call getchar() until it returns 0xffffffff which is the same as EOF.

undefined8 main(void)

{

long lVar1;

undefined8 *puVar2;

undefined8 local_818 [256];

uint local_14;

long local_10;

puVar2 = local_818;

for (lVar1 = 0xff; lVar1 != 0; lVar1 = lVar1 + -1) {

*puVar2 = 0;

puVar2 = puVar2 + 1;

}

local_10 = 0;

while( true ) {

local_14 = getchar();

if (local_14 == 0xffffffff) break;

add_char_to_map(local_818,local_14 & 0xff,local_10);

local_10 = local_10 + 1;

}

serialize_and_output(local_818);

return 0;

}

For every char, add_char_to_map is called.

void add_char_to_map(long param_1,byte param_2,undefined8 param_3)

{

undefined8 *puVar1;

long local_10;

local_10 = *(long *)(param_1 + (ulong)param_2 * 8);

puVar1 = (undefined8 *)malloc(0x10);

*puVar1 = param_3;

puVar1[1] = 0;

if (local_10 == 0) {

*(undefined8 **)((ulong)param_2 * 8 + param_1) = puVar1;

}

else {

for (; *(long *)(local_10 + 8) != 0; local_10 = *(long *)(local_10 + 8)) {

}

*(undefined8 **)(local_10 + 8) = puVar1;

}

return;

}

And finally; serialize_and_output is called.

void serialize_and_output(long param_1)

{

undefined8 local_28;

void **local_20;

void *local_18;

int local_c;

for (local_c = 0; local_c < 0xff; local_c = local_c + 1) {

local_20 = (void **)(param_1 + (long)local_c * 8);

local_28 = list_len(local_20);

fwrite(&local_28,8,1,stdout);

for (local_18 = *local_20; local_18 != (void *)0x0; local_18 = *(void **)((long)local_18 + 8)) {

fwrite(local_18,8,1,stdout);

}

}

return;

}

I tried to go through the code and rename variables to make it more clear, but I found all the pointer arithmetics hard to follow. It did help me somewhat obviouvsly, but I found it hard to visualize the data in my head before and after running it through the program.

Creating Files With Known Input

I shifted my attention to the file format and started analysing how my known input would look after running it through crush.

$ echo -n "test" | ./crush | xxd -a

00000000: 0000 0000 0000 0000 0000 0000 0000 0000 ................

*

00000320: 0000 0000 0000 0000 0100 0000 0000 0000 ................

00000330: 0100 0000 0000 0000 0000 0000 0000 0000 ................

00000340: 0000 0000 0000 0000 0000 0000 0000 0000 ................

*

000003a0: 0100 0000 0000 0000 0200 0000 0000 0000 ................

000003b0: 0200 0000 0000 0000 0000 0000 0000 0000 ................

000003c0: 0300 0000 0000 0000 0000 0000 0000 0000 ................

000003d0: 0000 0000 0000 0000 0000 0000 0000 0000 ................

*

00000810: 0000 0000 0000 0000 ........

Not very helpful, but a start.

$ echo -n "abc" | ./crush | xxd -a

00000000: 0000 0000 0000 0000 0000 0000 0000 0000 ................

*

00000300: 0000 0000 0000 0000 0100 0000 0000 0000 ................

00000310: 0000 0000 0000 0000 0100 0000 0000 0000 ................

00000320: 0100 0000 0000 0000 0100 0000 0000 0000 ................

00000330: 0200 0000 0000 0000 0000 0000 0000 0000 ................

00000340: 0000 0000 0000 0000 0000 0000 0000 0000 ................

*

00000800: 0000 0000 0000 0000 0000 0000 0000 0000 ................

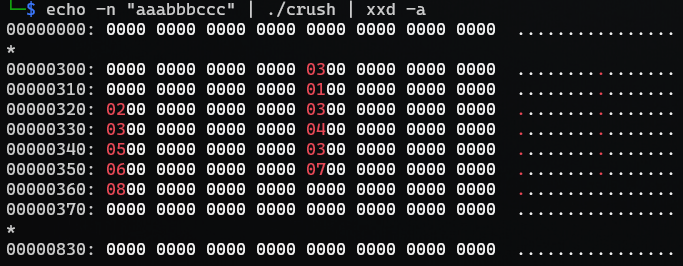

$ echo -n "aaabbbccc" | ./crush | xxd -a

00000000: 0000 0000 0000 0000 0000 0000 0000 0000 ................

*

00000300: 0000 0000 0000 0000 0300 0000 0000 0000 ................

00000310: 0000 0000 0000 0000 0100 0000 0000 0000 ................

00000320: 0200 0000 0000 0000 0300 0000 0000 0000 ................

00000330: 0300 0000 0000 0000 0400 0000 0000 0000 ................

00000340: 0500 0000 0000 0000 0300 0000 0000 0000 ................

00000350: 0600 0000 0000 0000 0700 0000 0000 0000 ................

00000360: 0800 0000 0000 0000 0000 0000 0000 0000 ................

00000370: 0000 0000 0000 0000 0000 0000 0000 0000 ................

*

00000830: 0000 0000 0000 0000 0000 0000 0000 0000 ................

Ok, I’m starting to see a pattern. I can see 0x03 three times, one for each group of letters; aaa, bbb and ccc. I also see that after 0x03 the following numbers; 0x00, 0x01 and 0x02 matches the index of my characters in the onput string. This is true for all three groups. It seems like we have a count and then indexes following the count.

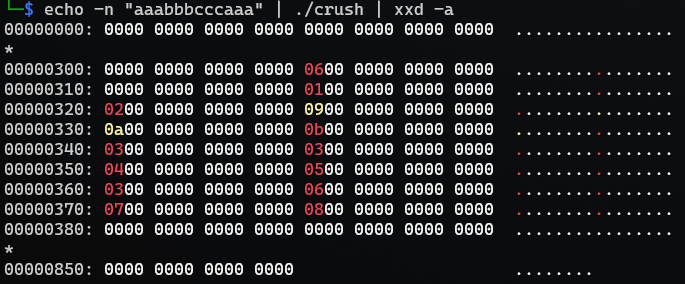

The input data aaabbbcccaaa seems to confirm the previous results:

Now we have six (6) a’s and the indexes; 0x0, 0x1, 0x2, 0x9, 0xa, 0xb matches the a’s in aaabbbcccaaa.

I see how this could be used to rebuild a string, but how do we know which characters to use? Since we have a lot of empty space in the file before our data, maybe the offset; 0x308 is used to identify the character somehow.

But the offsets aren’t fixed since the index count is variable. I guess the program just starts at an ASCII value and increments it for each group.

Another observation is that each value in the file format seems to be encoded as 8 bytes; 64 bits.

Let’s attempt to make a program and see if we can rebuild the input data based on message.txt.cz.

But first test to see if we can rebuild the aaabbbcccaaa string. Let’s write the output to a file:

$ echo -n "aaabbbcccaaa" | ./crush > test.cz

$ ll test.cz

-rw-r--r-- 1 hag hag 2136 Mar 10 03:02 test.cz

Success! I did mess around a bit with what character each group belonged to. I thought it might start at 0x20, which is the first printable ASCII character ( ; space). But it turned out to just start at 0, which explains all the NULL bytes at the start of the file.

My first attempt running my program on the message.txt.cz file resulted in trnmowzmrspreisytnorwryyubirrgl{zzvtrytpeswwsrstissgtoiznrxus}alytuisntwsnanrtrypzordmesyeslsptuptheestesirsly{wivisyreettyossrssstonntohtme}ttiirpntiznruelsinor{thvoryttshouontsessarpaslzer3}rganrzert1:Sousosutslyoushsuturittsonotpltunnnswnntstwsttnkestst. Which at least seemed promising and then I remembered I forgot to read all count and index values as 64 bit integers.

// Changing:

var index = data[i + 8];

// To:

var index = BitConverter.ToInt64(data, i + 8);

Fixed it!

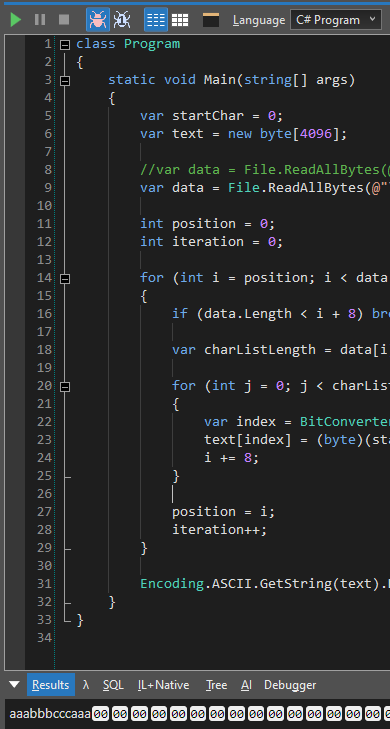

Solve Program

class Program

{

static void Main(string[] args)

{

var startChar = 0;

var text = new byte[4096];

var data = File.ReadAllBytes(@"message.txt.cz");

//var data = File.ReadAllBytes(@"test.cz");

int position = 0;

int iteration = 0;

for (int i = position; i < data.Length; i += 8)

{

if (data.Length < i + 8) break;

var charListLength = data[i];

for (int j = 0; j < charListLength * 8; j += 8)

{

var index = BitConverter.ToInt64(data, i + 8);

text[index] = (byte)(startChar + iteration);

i += 8;

}

position = i;

iteration++;

}

Encoding.ASCII.GetString(text).Dump();

}

}

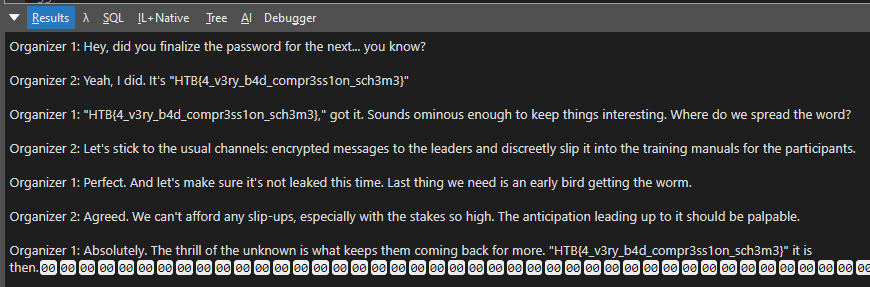

Resulting Text

Organizer 1: Hey, did you finalize the password for the next... you know?

Organizer 2: Yeah, I did. It's "HTB{4_v3ry_b4d_compr3ss1on_sch3m3}"

Organizer 1: "HTB{4_v3ry_b4d_compr3ss1on_sch3m3}," got it. Sounds ominous enough to keep things interesting. Where do we spread the word?

Organizer 2: Let's stick to the usual channels: encrypted messages to the leaders and discreetly slip it into the training manuals for the participants.

Organizer 1: Perfect. And let's make sure it's not leaked this time. Last thing we need is an early bird getting the worm.

Organizer 2: Agreed. We can't afford any slip-ups, especially with the stakes so high. The anticipation leading up to it should be palpable.

Organizer 1: Absolutely. The thrill of the unknown is what keeps them coming back for more. "HTB{4_v3ry_b4d_compr3ss1on_sch3m3}" it is then.

Flag:

HTB{4_v3ry_b4d_compr3ss1on_sch3m3}